Can Food Really Influence the Microbiome?

Yes! Spoiler alert

But first, let’s ensure we are all on the same page with some background knowledge before we deep dive.

The Microbiome = the trillions of microorganisms, including fungi, viruses, parasites, and bacteria that inhabit the human gut, skin, and other mucosal environments. Advancements in gut-specific science have shown that the gut microbiome plays a role in multiple functions ranging from sleep, nutrition, mental health, metabolism and even immunity(1-3). For the purposes of today’s post, let’s focus the conversation specifically on the gut microbiome.

THE MICROBIOME & THE IMMUNE SYSTEM

The microbiome and the human body seem to play nice in the sandbox together, or in other, more science-y words, have a tendency toward “mutualism and homeostasis”. However, this ability for the body and the microbiome to be compatible requires proper functioning of the immune system, which conveniently exists mostly in the GI tract. When the immune system and the microbiome are communicating effectively, this results in protective outcomes, like proper regulation of infection(4). Conversely, with IBD, changes in the gut microbiome appear to alter the immune system in a way that makes the immune system respond abnormally, or hyperactively. These changes arise from a number of possible factors, most commonly referenced are: antibiotic use, where someone lives, diet, and how these factors interact with genetics(5).

A HEALTHY MICROBIOME

The challenge: science hasn’t told us the full story about the exact interactions between the microbiome and its environment, especially in regards to diet and the immune system(6). Think of the microbiome like outer space, or the deepest places in the ocean: we are only beginning to understand this new frontier. There are over 100 trillion microbes living in the gut microbiome(7). To make matters more complex, each individual has their own unique, dynamic combination of microbes. As a result, a “healthy” microbiome is difficult to define and generalize to a population. Additionally, what might be defined as a “healthy” microbiome, if such a definition existed, may differ widely between countries, cultures, communities, neighborhoods, and whether someone is young or elderly, wealthy or impoverished, solitary or social since each of these circumstances influences microbial composition(8). Projects like the US Human Microbiome Project (HMP) have ongoing research to attempt to map, understand, and more closely identify what a “healthy” microbiome looks like, but with over 100 trillion species of microbes to consider, this is certainly a place of new discovery with ever-evolving, emerging research(9).

Would I benefit from microbiome testing?

Commercial microbiome tests might be useful one day, but for now, here are some highlights to consider before investing your time and energy into microbiome kits:

There are trillions of species of bacteria remaining in the microbiome whose functions we cannot yet define(10).

Science has not yet provided a snapshot of a “healthy” microbiome, and this definition may vary greatly between populations. A microbial composition that is predictive of disease has not yet been identified either.

Stool studies are not able to provide an accurate picture of what is happening on a mucosal level in the GI tract.

Just because a test provides a large amount of information does not mean that it is reliable, and it might not be useful in identifying solutions.

Some microbiome testing kits will report bacterium as “good” or “bad” but most bacteria relies on its environment and its interaction with other bacteria to determine its behavior(11).

What about probiotic supplements?

Glad you asked- there’s a whole blog post about probiotics right here!

In their 2023 review of research, The British consensus guidelines suggest that in some patients with mildly active ulcerative colitis, taking specific probiotics alongside prescribed medication (mostly 5-ASAs) may support induction of remission. Additionally, probiotics with specific strains may help maintain remission in chronic relapsing pouchitis in people who live with a j-pouch. However, there’s no evidence to suggest that the same is true for Crohn’s disease(12)

What kinds of foods should I be eliminating to help my microbiome?

People with IBD are at an increased risk for malnutrition from chronic inflammation, malabsorption, and/or food restriction, all of which have shown to decrease microbiome diversity. So, let’s flip this question to ask about which foods to include to influence the microbiome. As far as the research has shown, increased microbiome diversity has been associated with better GI functionality and overall health(13-14). However, if you don’t feel like adding foods to your diet is a safe or available goal right now, that’s okay; please don’t hesitate to reach out for support!

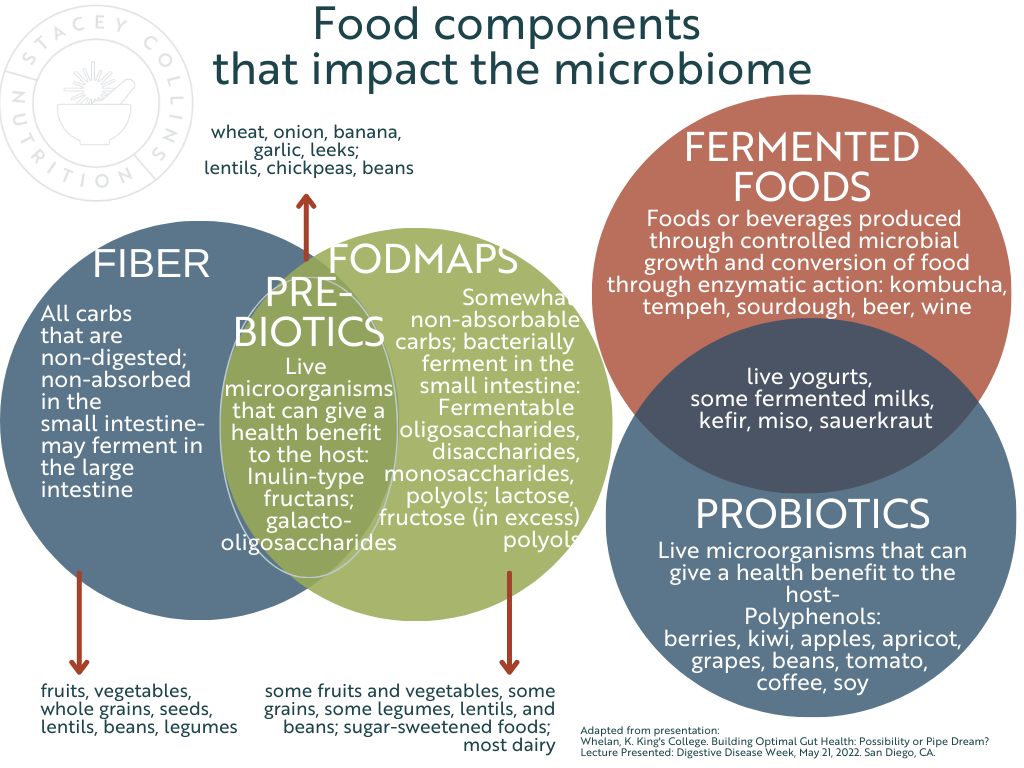

Below are a few categories and sources of foods that are often categorized together and blamed as common GI-condition culprits, when in actuality they have important, unique functions in the microbiome.

Just as we explored how single microbes usually can’t be labeled in dichotomous categories, such as “good” or “bad”…the same is true with food. If we zoom out from a single ingredient, or a single supplement, we see an important benefit called food synergy. Consuming a variety of foods exerts an effect between and within nutrients of foods that may have an even greater microbial impact than once single ingredient(15).

*If you find yourself in need of a medical diet right now and food variety feels like an unavailable goal, seek guidance from a dietitian experienced with IBD to ensure nutritional adequacy of your medical diet. Dietitians can help with safe, timely re-introduction of foods to find your optimal, individualized eating pattern that is supportive of your health and your quality of life.

SOME KEY TAKEAWAYS FOR REAL-LIFE APPLICATION:

The microbiome is real, and it’s dynamic! It is influenced by a number of different factors and how they interact with genetics.

Research is still seeking to define a “healthy” microbiome, since functions of trillions of microbes are still in question

Microbiome testing is still in its infancy, and it is not clinically useful…yet

Food first! Save the dollars that you’d spend on probiotic supplements and consider how you can add a variety of foods into your diet that provide food synergy and support microbiome diversity

Work with a professional if you’re unsure where to begin

Frequently Asked Questions About Food and the Gut Microbiome

-

The gut microbiome consists of trillions of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites, residing in the human gastrointestinal tract. These microbes play essential roles in various bodily functions, such as digestion, immunity, and overall health

-

A well-balanced gut microbiome supports proper immune function by maintaining mutualism and homeostasis. Disruptions in the microbiome can lead to abnormal immune responses, contributing to conditions like Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD).

-

Yes, diet significantly influences the composition and function of the gut microbiome. Dietary choices can impact microbial diversity and activity, affecting overall health.

-

Defining a 'healthy' microbiome is challenging due to individual variability and environmental factors. Ongoing research aims to better understand the characteristics of a balanced microbiome.

-

Currently, commercial microbiome tests have limitations. The vast diversity of microbes and the lack of a clear definition of a 'healthy' microbiome make it difficult to interpret test results accurately.

-

Probiotics may benefit certain individuals, especially those with specific conditions like mildly active ulcerative colitis. However, their effectiveness varies, and it's essential to consult with a healthcare provider before starting any probiotic regimen.

References:

1. Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Are we really vastly outnumbered? revisiting the ratio of bacterial to host cells in humans. Cell. 2016;164:337–340.2. Hacquard S, et al. Microbiota and host nutrition across plant and animal kingdoms. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:603–616.3. Lynch JB, Hsiao EY. Microbiomes as sources of emergent host phenotypes. Science. 2019;365:1405–1409.4. Dethlefsen L, McFall-Ngai M, Relman DA. An ecological and evolutionary perspective on human-microbe mutualism and disease. Nature. 2007;449:811–818.5. Zhang M, et al. Interactions between intestinal microbiota and host immune response in inflammatory bowel disease. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:942.6. Sharon I, Quijada NM, Pasolli E, et al. The Core Human Microbiome: Does It Exist and How Can We Find It? A Critical Review of the Concept. Nutrients. 2022;14(14):2872. Published 2022 Jul 13. doi:10.3390/nu141428727. Guinane CM, Cotter PD. Role of the gut microbiota in health and chronic gastrointestinal disease: understanding a hidden metabolic organ. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6(4):295-308. doi:10.1177/1756283X134829968. Ding T, Schloss PD. Dynamics and associations of microbial community types across the human body. Nature. 2014 Apr 16. PMID 247399699. Integrative HMP (iHMP) Research Network Consortium. The Integrative Human Microbiome Project: dynamic analysis of microbiome-host omics profiles during periods of human health and disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16(3):276-289. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2014.08.01410. Thomas AM, Segata N. Multiple levels of the unknown in microbiome research. BMC Biol. 2019; 17(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s12915-019-0667-z.11. Staley, C., Kaiser, T. & Khoruts, A. Clinician Guide to Microbiome Testing. Dig Dis Sci 63, 3167–3177 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-018-5299-612. Lomer MCE, Wilson B, Wall CL. British Dietetic Association consensus guidelines on the nutritional assessment and dietary management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2023;36(1):336-377. doi:10.1111/jhn.1305413. Schröder L, Kaiser S, Flemer B, et al. Nutritional Targeting of the Microbiome as Potential Therapy for Malnutrition and Chronic Inflammation. Nutrients. 2020;12(10):3032. Published 2020 Oct 3. doi:10.3390/nu1210303214.Mills S., Lane J.A., Smith G.J., Grimaldi K.A., Ross R.P., Stanton C. Precision Nutrition and the Microbiome Part II: Potential Opportunities and Pathways to Commercialisation. Nutrients. 2019;11:1468. doi: 10.3390/nu1107146815. Hu F.B. Dietary pattern analysis: A new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2002;13:3–9. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200202000-00002.